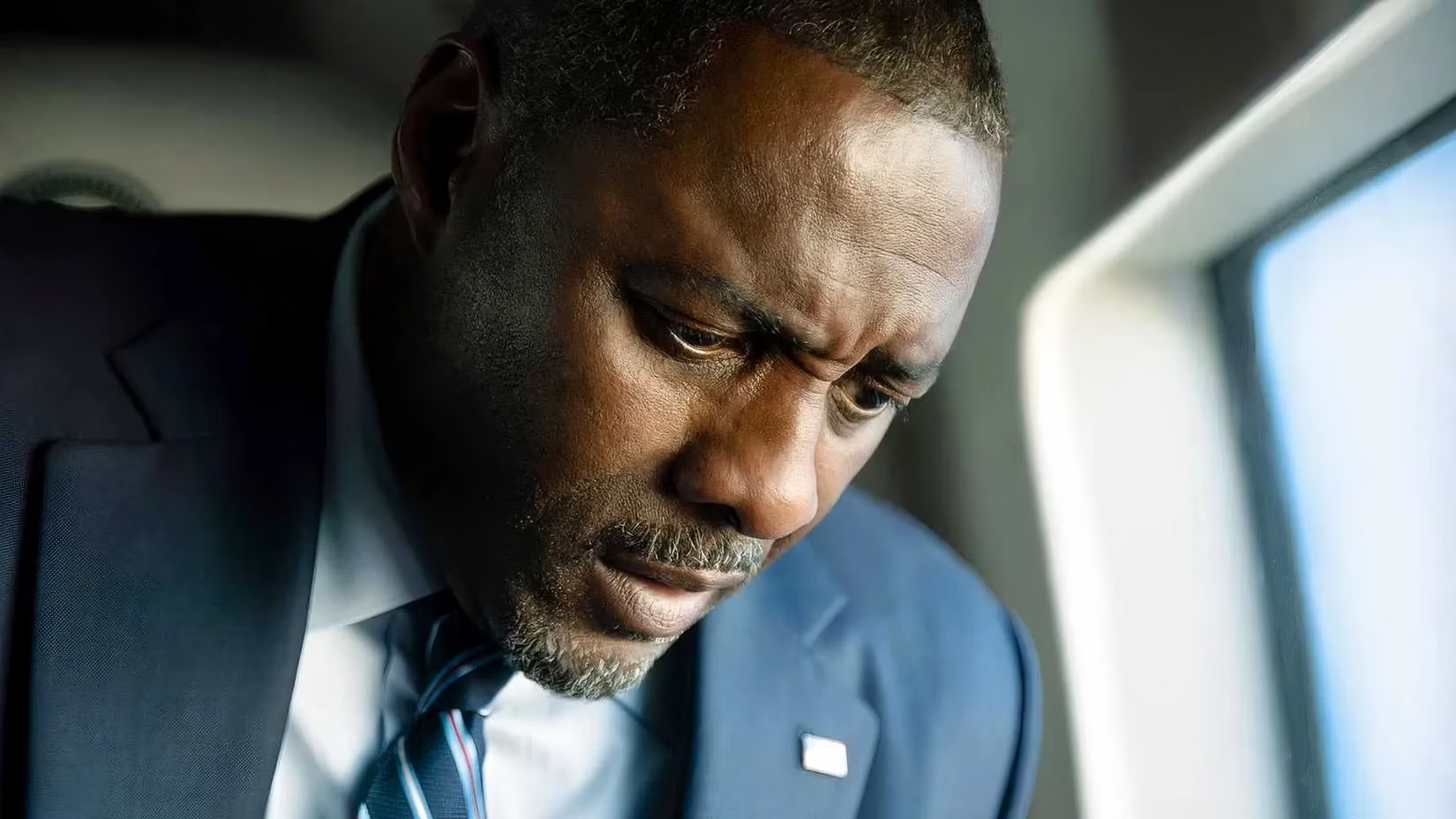

In the cinematic landscape of 2026, few films have sparked as much debate as Kathryn Bigelow's 2025 Netflix thriller, A House of Dynamite. The film, which follows a sprawling cast of U.S. government and military officials grappling with an inbound nuclear missile targeting Chicago, was lauded for its terrifying realism but left audiences divided with its ambiguous, open-ended finale. The story freezes at the pivotal moment: the missile is in the air, its impact unknown, and the President of the United States, portrayed by Idris Elba, is frozen in a moment of anguished contemplation, his finger hovering over the proverbial button. The credits roll before we learn of Chicago's fate or the President's retaliatory decision, a choice that has ignited fierce discussion among viewers and critics alike. 🎬

🧨 The Cameron Defense: "The Only Possible Ending"

Enter James Cameron, the visionary filmmaker behind Titanic and Avatar. In a recent interview, Cameron fervently defended Bigelow's controversial conclusion, calling it "the only possible ending." He recently had dinner with Bigelow and told her he "utterly defends that ending." For Cameron, the ambiguity isn't a flaw; it's the entire thesis of the film. He draws a parallel to the classic short story "The Lady or the Tiger?," where the reader never learns what lies behind the chosen door. The point, he argues, is the unbearable tension of the choice itself, not its resolution.

Cameron elaborates that from the moment the missile launch is detected, "the outcome already sucked. There was no good outcome, and the movie spent two hours showing you there is no good outcome." The film's purpose, he reiterates, is a broad, chilling cautionary tale. It aims to illustrate the existential danger of the world's nuclear arsenal and the terrifying reality that, in the American system, the fate of billions rests on the split-second decision of a single individual. A House of Dynamite becomes a cinematic pressure cooker, designed not to provide answers but to make the audience viscerally feel the weight of a question with no good answers. Cameron's stance is clear: the film's power lies in its refusal to offer catharsis, leaving the audience to sit with the dread—a feeling as pervasive and unsettling as a low-frequency hum in an empty room.

💣 A Tale of Two Nuclear Narratives: Dynamite vs. Oppenheimer

Cameron's defense inevitably invites comparison to another recent nuclear-themed blockbuster: Christopher Nolan's Oppenheimer. Interestingly, Cameron has been famously critical of Nolan's film, labeling its approach a "moral cop-out" for not visually depicting the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The irony is palpable, as A House of Dynamite also avoids showing a nuclear detonation. So, what's the difference?

Cameron's argument hinges on context and intent. Oppenheimer is a historical drama about the bomb's creation; not showing its consequences, in Cameron's view, lets the audience off the hook. A House of Dynamite, however, is a speculative thriller about a present-day crisis. Its ambiguity is forward-looking and participatory. The unseen explosion in Dynamite isn't an omission—it's a looming shadow, a sword of Damocles suspended by a single, fraying thread. The film forces viewers to project their own fears into that void, making the terror personal and immediate. Where Oppenheimer looks back at a historical pivot point, A House of Dynamite holds up a mirror to our current, fragile reality.

🎭 The Ensemble in the Eye of the Storm

Beyond its philosophical core, the film is powered by a stellar ensemble cast that brings human faces to the bureaucratic nightmare. The film's tension is woven through their performances:

-

Idris Elba as POTUS: Carries the unbearable weight of ultimate decision-making. His performance is a masterclass in contained agony.

-

Rebecca Ferguson as Captain Olivia Walker: Embodies the military precision and mounting desperation on the front lines of the crisis.

-

Anthony Ramos, Tracy Letts, Jared Harris: Represent various strata of the government machinery, each reacting to the crisis with fear, calculation, or grim duty.

Their intertwined stories create a mosaic of modern warfare, where strategy rooms and satellite feeds become the new battlefield. The film's genius is in showing how a global catastrophe gets filtered through conference calls, procedural protocols, and isolated individuals staring at screens, their collective fate hanging in the balance like a single, perfect dewdrop on a spider's web at dawn.

🔍 Why the Ending Works: The Unanswered Question as a Call to Action

For those frustrated by the lack of closure, Cameron and Bigelow's message is that closure is an illusion in the nuclear age. The film isn't about what happens to Chicago; it's about the system that allowed the crisis to occur. The open ending is a deliberate narrative gambit, transforming the movie from a passive viewing experience into an active engagement with our world. It asks the audience: What would you do? What should we do?

Cameron explicitly connects this to civic duty: "That's the world we live in and we need to remember that when we vote next time." The film becomes a stark reminder that the power to authorize nuclear strikes is vested in political leaders chosen by the populace. The final, frozen moment of presidential indecision is, in essence, a reflection of our own collective responsibility—a responsibility as vast and intricate as the root system of an ancient, towering tree, hidden from view but fundamental to everything above ground.

🎬 Final Verdict: A Necessary Discomfort

In 2026, A House of Dynamite stands as a bold, uncomfortable, and essential piece of cinema. It forgoes the easy satisfaction of a resolved plot for the harder, more important work of provoking thought and debate. James Cameron's robust defense underscores that sometimes, the most powerful statement a story can make is to point at a terrifying reality and refuse to look away, leaving the audience to sit in the silence of its implications.

Whether you love or hate the ending, it has achieved its goal: making the abstract, world-ending threat of nuclear weapons feel terrifyingly personal and urgently real. The film doesn't end with a bang or a whimper, but with a question mark—a question mark that hangs over every one of us. In that sense, the movie's true detonation happens not on screen, but in the mind of the viewer long after the screen has gone dark. 💥

Comments