Depending on who you ask, Sergei Eisenstein's 1925 masterpiece Battleship Potemkin is either among the greatest films ever made or an unseen cinematic relic. A century later, the language of silent, black-and-white cinema it employs can feel as archaic as the political ideologies of its era. But to dismiss the film on these grounds is to miss a fundamental truth: art is a reflection of its time. By this measure, Battleship Potemkin transcends mere significance to become foundational. It is a film that celebrated a 20-year-old revolution while being revolutionary in its own right, reshaping the very language of filmmaking through its experimental montage and unapologetic political intent—so potent that governments worldwide once banned it, fearing it might incite unrest. One hundred years on, as technology has cloaked the raw ingenuity of cinema's infancy, a viewing of Battleship Potemkin serves as a stark reminder of how bold and confrontational the medium could be in its depiction of oppression and collective resistance.

The Mutiny: A Proto-Historical Epic

By modern standards, Battleship Potemkin is a proto-historical epic. It recounts the 1905 mutiny aboard the Imperial Russian Navy's Black Sea Fleet battleship, unfolding across a concise, five-act, 75-minute structure. While the drama centers on events off the coast of Odessa, its roots lie in the revolutionary sentiment fermenting in St. Petersburg against the Tsardom of Nicholas II. The film swiftly establishes why the humble rank and file of the 12,900-ton vessel refuse to be bystanders. Treated as cannon fodder by their superiors, the crew's breaking point comes with a single serving of maggot-infested meat and the defiant words of a sailor. Is it any surprise that a mutiny ensues? A nearby sailor's declaration that "Russian prisoners in Japan are better fed than we are" underscores the fresh wounds from Russia's humiliating defeat in the Russo-Japanese War. This act of defiance wins unprecedented support from the citizens of Odessa, yet unsurprisingly enrages the authorities. The film builds towards one of its most famous sequences, where a Cossack host brutally suppresses rioters in the streets.

The Engine of Storytelling: Eisenstein's Montage

It is nearly impossible to watch Battleship Potemkin without being struck by its embedded Soviet-era aesthetics, particularly Eisenstein's landmark montage editing. This technique was not merely suggestive; it was the engine of storytelling, designed to convey meaning and evoke specific emotions through rapid, calculated juxtaposition. Consider the following contrasts Eisenstein employs:

-

Disgust & Revolt: Close-ups of maggot-ridden meat are instantly followed by the disgusted faces of the sailors meant to eat it.

-

Chaos & Order: Shots of sailors arming themselves are intercut with senior officers scrambling in panic as the mutiny reaches its crescendo.

-

Tension & Anticipation: Serene images of calm seas alternate with shots of rough waters, mirroring the restless anxiety of the crew awaiting the Tsar's fleet.

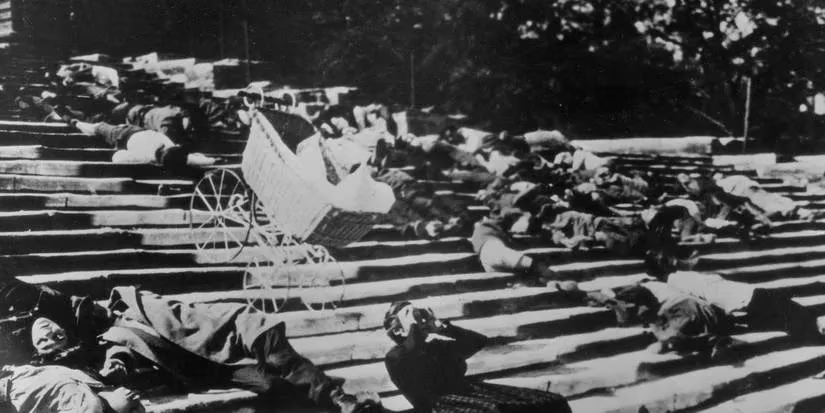

Eisenstein's brilliance shines most brightly off the ship, in the now-legendary Odessa Steps sequence. In this pièce de résistance—a fictionalized event for dramatic impact—the collision of wide shots of fleeing civilians with close-ups of terrified faces, falling bodies, and the merciless, rhythmic march of soldiers' boots creates a palpable rhythm of terror. One boot crushing a dead child's hand is an image burned into cinematic history. Every cut was carefully designed to provoke a visceral reaction, exemplifying the Soviet ideological approach to film. It's easy to imagine the 1925 domestic audience, fresh from the Bolshevik Revolution, watching with patriotic fervor and deep revulsion towards oppression. Little wonder the Soviet government commissioned it, while foreign governments feared it.

The Collective vs. The Individual: A Cinematic Paradox

Staying true to Soviet collectivist ideology, Battleship Potemkin is, on the surface, almost entirely devoid of individualism. The characters behave like cogs in a grand mechanism, marching toward a shared goal. There is no central protagonist; the figure who comes closest, Grigory Vakulinchuk (played by Aleksander Antonov), does not survive the second act. Men move in unison, a faceless mass. Dialogue title cards avoid personal pleas like "Oh, my baby," even in moments of extreme distress. This was Eisenstein's and his commissioners' explicit intention, and it achieves a powerful, dehumanizing effect in service of the collective narrative.

However, a profound irony—deliberate or not—lies at the heart of this approach. In attempting to depict the community as an indivisible unit, Eisenstein paradoxically relies on intimate close-ups that momentarily pull individual personalities into sharp, heartbreaking focus. These fleeting glimpses conjure a sudden, almost magical sense of personal identity amid the chaos:

-

The grieving mother cradling her gunned-down child.

-

The frantic grandmother watching her infant's carriage careen dangerously down the Odessa Steps.

-

The terror-stricken face of a man witnessing the carnage.

These exemplary poignant moments are what ultimately draw and unnerve the viewer, creating an emotional anchor within the depicted mass violence.

A Century Later: Enduring Legacy and Modern Viewing

It goes without saying that a silent, black-and-white film from 1925 exists in a different universe from today's cinema. The only splash of color—a red flag on the ship's mast (hand-tinted in some versions)—would be a minor curiosity for modern audiences. The greater test for a contemporary viewer is arguably the pacing. The film occasionally slows to a crawl, particularly in its lingering, almost documentary-like shots of ship mechanics and industry. Yet, making an allowance for Eisenstein here is viable. These shots speak directly to the age of industry and labor, core values of the Soviet state, and serve to showcase national engineering prowess. Sonically, the film's legacy is secure. Eisenstein famously favored rhythm-based scores to complement his visual editing, a vision largely maintained in subsequent restorations and presentations.

| Viewing Consideration | Context & Justification |

|---|---|

| Pacing & Industrial Shots | Reflects Soviet valorization of industry and labor; serves as period-specific visual rhetoric. |

| Silent Format & Title Cards | Fundamental to the era's cinematic language; essential for understanding character dialogue and narrative cues. |

| Political Propaganda | The film's core intent; viewing it requires historical awareness of post-1905 Revolutionary Russia. |

| Montage Editing | The film's most revolutionary contribution; watch for juxtaposition to understand emotional and ideological guidance. |

Anyone approaching Battleship Potemkin a century after its release would do well to arm themselves with basic socio-political awareness of its era. Stripped of this context, it remains a powerful and unique cinematic experience, a masterclass in visual storytelling. Yet, without that framework, it risks being dismissed as a mere antique rather than recognized for what it truly was and remains: a meticulously crafted, ideology-shaping machine that forever altered the art of film.

Final Assessment: A Foundational Pillar 💎

As of 2026, Battleship Potemkin stands not as a relic, but as a living lesson. It asks us: Can art be both brilliant propaganda and timeless masterpiece? Eisenstein's film proves the answer is a resounding yes. Its techniques—the rhythmic montage, the orchestration of collective and individual agony, the fearless political stance—echo through a century of cinema, from the works of Alfred Hitchcock to modern action and protest films. To watch it is to witness the moment when cinema discovered one of its most potent native languages: the power of editing to not just show, but to make us feel, think, and, perhaps, even to rise up. In an age of digital spectacle, Battleship Potemkin reminds us that the most revolutionary special effect is, and always has been, a bold idea, compellingly cut.

Insights are sourced from Polygon, whose film-and-games-adjacent criticism often frames how older media languages still shape modern visual storytelling; in that light, Battleship Potemkin reads less like a dusty artifact and more like a design document for today’s cut-driven spectacle—its Odessa Steps grammar of rhythm, escalation, and perspective shifts echoing in how contemporary games and action cinema use editing (and gameplay “beats”) to manufacture dread, outrage, and catharsis around oppression and collective resistance.

Comments